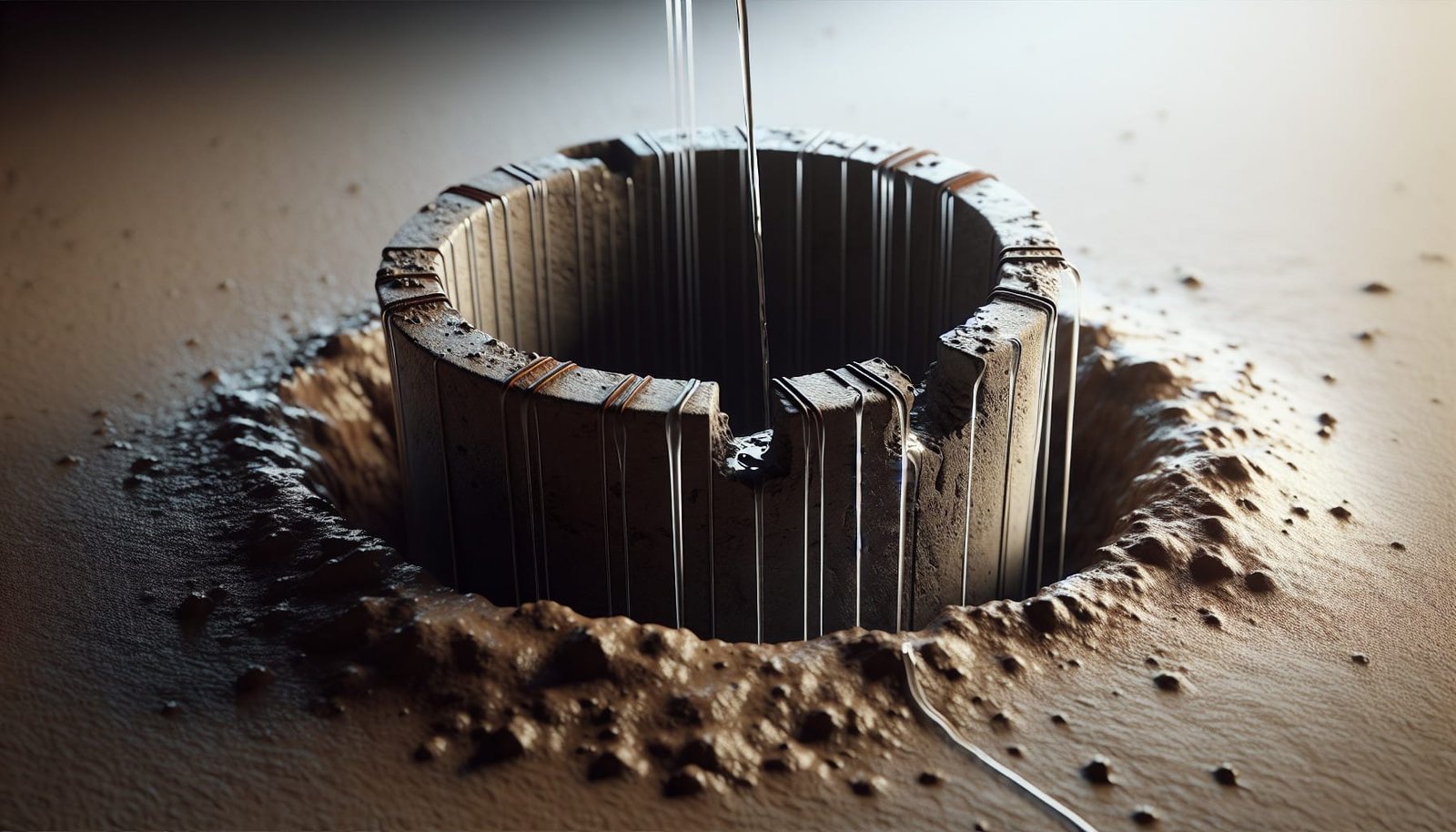

?Is your well casing cracked and putting your household water at risk?

How Do I Know If My Well Casing Is Cracked?

You rely on your well for safe water, and a cracked well casing can threaten that supply. This article explains how to identify a cracked well casing, what signs to look for, how to inspect and test your well, and what actions to take if you suspect damage.

What is a well casing and why it matters

A well casing is the structural lining installed in the drilled well to keep the hole open, prevent collapse, and protect groundwater from surface contamination. It also guides the pump system and helps maintain sanitary conditions around your water source.

If the casing is compromised, contaminants like surface water, sediment, or chemicals can enter the well. You’ll want to address casing issues quickly to protect your health, plumbing equipment, and property value.

Common types of well casing materials

Different materials have different strengths, weaknesses, and lifespans. The casing material affects how and why cracks occur.

- Steel: Very common in older wells; strong but prone to corrosion over decades.

- PVC (plastic): Resistant to corrosion and lighter but can crack from freezing, UV exposure, or mechanical impact.

- Concrete: Often used for lined wells or sealed annuli; can crack under ground movement or from chemical attack.

- Stainless steel or special alloys: Used for modern or specialized installations; more resistant to corrosion but more expensive.

Typical lifespan of well casings

You should expect different service lives depending on material and conditions. A well-cared-for PVC casing can last many decades, while steel casings may begin corroding within 20–40 years in aggressive soils. Ground movement, groundwater chemistry, installation quality, and maintenance affect longevity.

Causes of well casing cracks

Understanding causes helps you identify likely damage mechanisms and select appropriate repairs. Cracks and failures often come from:

- Corrosion: Particularly for steel casings exposed to acidic or microbial-influenced waters.

- Freezing and thawing: Surface or shallow pipes and casings can be damaged by frost heave or ice.

- Ground movement: Soil settling, earthquakes, or heavy traffic can stress the casing.

- Improper installation: Poor seals, inadequate grout, or damaged casing during drilling.

- Mechanical impact: Excavation or heavy equipment near the wellhead can dent or crack casing.

- Chemical attack: High acidity, sulfates, or other aggressive chemicals in groundwater.

- Age and fatigue: Long-term wear and cumulative stress can lead to cracks.

Signs that suggest your casing may be cracked

Cracked casings can produce a range of symptoms. You usually won’t see the crack itself without specialized inspection, but you can infer damage from indicators.

- Turbid or muddy water: Sudden or persistent cloudiness often means surface water or sediment is entering the well.

- Sudden changes in water level: Rapid decline or erratic drawdown when you use water could indicate leakage.

- New or recurring bacterial contamination: Repeated positive coliform tests suggest compromised sanitary protection.

- Unpleasant tastes or odors: Surface runoff, organic matter, or chemicals can alter taste and smell.

- Visible damage at the wellhead: Bent, corroded, or missing well caps and seals point to possible pathways for contamination.

- Sediment in plumbing or increased pump wear: Sand, grit, or premature pump failures can indicate casing deterioration.

- Wet or saturated area near the well: Water pooling or damp soil near the wellhead might indicate casing leaks or failed seals.

- Air or gurgling noises from plumbing: Unusual sounds can reflect irregular flows or ingress of air through cracks.

How to perform a basic visual inspection

A careful visual check around the wellhead is a good initial step and often reveals obvious problems. Only do non-invasive inspections unless you’re trained.

- Walk the perimeter: Look for standing water, erosion, or soil disturbance near the well.

- Inspect the well cap and seal: Ensure the cap is securely fastened and the sanitary seal (grout or concrete) is intact.

- Check for corrosion or external cracks: Rust, flaking metal, or visible splits indicate possible casing failure.

- Look for vegetation or animal entry points: Burrowing animals or roots can damage the well surroundings.

- Examine plumbing and pump wiring: Exposed wiring or compromised connections suggest previous impacts.

Always observe safety: keep tools clear of electrical wiring, and don’t remove the cap unless you know how to avoid contaminating the well.

Advanced inspection methods professionals use

If visual cues suggest problems or you want confirmation, professionals use specialized tools and tests to detect casing defects.

- Downhole camera (video logging): Provides a visual record of the internal casing condition and any cracks, joints, or debris.

- Acoustic or ultrasonic testing: Detects wall thinning, discontinuities, and corrosion without removing components.

- Pressure testing: Isolates sections and checks for leaks under controlled pressure.

- Borehole televiewer or caliper logs: Measure diameter changes and identify distortions or fractures.

- Geophysical methods: Electrical or magnetic surveys can reveal casing discontinuities or subsurface pathways.

- Dye tracer or slug tests: Identify leak paths and communicate between surface water and well.

These methods are more accurate than DIY inspections and can help plan appropriate repairs.

Step-by-step DIY well casing check list

You can perform safe, basic checks to identify issues requiring professional attention. These steps are not a substitute for certified testing when contamination or structural failure is suspected.

- Gather basic safety gear: gloves, eye protection, and a flashlight.

- Turn off power to the pump: avoid electrical hazards while checking the wellhead.

- Walk the area around the well: look for standing water, erosion, or recent construction activity.

- Inspect well cap and seal: ensure the cap is intact, sealed, and vermin-proof.

- Look for corrosion or exterior damage: visually assess the casing above ground for rust or cracks.

- Run a faucet inside your house: observe clarity, flow, and pressure. Note any changes.

- Check for sediment in water: use a clear container to catch and inspect water for grit.

- Smell and taste test cautiously: only as a preliminary indicator—avoid ingesting suspicious water.

- Record findings and take photos: document visible issues to show to a professional.

If you find anything unusual—contamination, visible cracks, pump failure, or suspicious water—you should contact a licensed well contractor or public health authority for testing.

When you should call a professional

If you detect any of these conditions, seek professional help:

- Positive bacteria test (coliform or E. coli)

- Sudden water discoloration, foul odor, or unusual tastes

- Visible casing damage or missing/worn sanitary seal

- Rapid, unexplained water level changes

- Pump problems possibly related to casing damage

- Evidence of contamination after flooding or nearby spills

- Structural collapse or subsidence near the well

Professionals have the tools and training for safe, accurate diagnosis and repairs.

Water testing: what to test for and why

Testing your well water helps determine if a cracked casing has allowed contaminants in. Routine testing is vital, especially after events like flooding, earthquakes, or nearby construction.

Table: Recommended water tests and what they indicate

| Test | What it detects | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Total coliform / E. coli | Bacterial contamination | Indicates surface or septic system contamination; immediate health risk if positive |

| Nitrate/Nitrite | Agricultural or sewer contamination | High levels harm infants and indicate surface infiltration |

| TDS (Total Dissolved Solids) | Mineral and salt content | Elevated TDS can indicate groundwater mixing or contamination |

| Turbidity | Suspended particles | Suggests sediment or surface runoff entering the well |

| pH | Acidity/alkalinity | Corrosive water can accelerate casing corrosion |

| Iron, Manganese | Metal concentrations | Can indicate corrosion or natural mineral dissolution |

| Sulfate/Chloride | Salts and chemical loading | High levels can suggest contamination or saline intrusion |

| Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) | Petroleum products, solvents | Indicates chemical spills or surface contamination |

| Lead/Copper | Metals from plumbing or corrosion | Public health concern; may be mobilized by corrosive water |

Test frequency: Basic bacterial tests annually; more frequent tests after flooding, repair work, or if you notice changes in water quality.

Interpreting test results

- Any positive E. coli is a red flag: stop using water for drinking/cooking until treated and fixed.

- Elevated nitrates (>10 mg/L) and certain VOCs require immediate alternative water supply and professional remediation.

- High iron or manganese often points to corroding materials or natural geochemistry—could indicate casing or casing joint problems.

- A sudden increase in turbidity or TDS after a storm suggests surface infiltration through compromised casing or seals.

Coordinate testing with certified labs and retain records for future comparison.

Repair options for a cracked well casing

Repair strategy depends on the crack’s location, severity, and the casing material. A professional will recommend the best approach after inspection.

- Grouting and sealing: Inject grout or sanitary seal to fill cracks near the surface or annulus.

- Casing patch: Metal sleeves or epoxy patches can seal localized damage.

- Lining or re-casing: Install a new inner casing or liner (PVC or steel) to extend service life without drilling a new well.

- Well rehabilitation: Cleaning, redeveloping, and disinfecting the well after repair to restore sanitary conditions.

- Full replacement: Drill a new well when damage is extensive or repair is not cost-effective.

- Well abandonment and replacement: If contamination is severe and irreparable, proper abandonment and new well construction may be required.

Pros and cons of repair methods

Table: Common repair approaches and considerations

| Repair method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Grouting/sealing | Relatively inexpensive; quick | May not fix deep or extensive cracks |

| Patching | Targeted repair of localized damage | May not be durable for widespread failure |

| Lining/re-casing | Extends well life; protects against contamination | More costly; may reduce well diameter and yield |

| Full replacement | Long-term solution; modern materials | Most expensive; requires drilling and permits |

| Abandonment + new well | Eliminates contaminated source | Costly and time-consuming; requires proper disposal of old well |

Typical cost ranges

Costs vary widely by region, well depth, and complexity. Use these ranges as general guidance; obtain quotes from local contractors.

Table: Rough cost estimates (USD)

| Service | Typical cost range |

|---|---|

| Basic surface seal repair/grouting | $300 – $1,500 |

| Localized casing patch | $500 – $2,000 |

| Lining/re-casing (partial) | $2,000 – $6,000 |

| Full re-casing or relining | $5,000 – $15,000 |

| New well drilling (residential) | $5,000 – $20,000+ |

| Comprehensive water testing | $100 – $500 per panel |

Prices depend on depth, accessibility, material, and local labor rates. Always get multiple estimates and check contractor credentials.

Emergency steps if you suspect a cracked casing

If you suspect casing failure that threatens water safety, take immediate actions to limit health risks.

- Stop drinking and cooking with well water until tested or treated.

- Use an alternate safe water supply (bottled water, neighbor, or municipal source).

- Turn off the pump if advised by a professional to prevent drawing further contaminated water.

- Sample and test the water promptly, focusing on bacteria and likely contaminants.

- Contact a licensed well contractor and local public health agency for guidance.

- Avoid repairing the well yourself if contaminants or structural damage are suspected. Improper intervention can make contamination worse.

Sanitary wellhead and prevention measures

Prevention reduces the risk of casing damage and contamination. Regular attention keeps your well functional.

- Maintain a secure, sealed well cap and sanitary grout around the casing.

- Keep a 50-foot clear zone around the well free of potential contaminants like fuel tanks, septic systems, or animal enclosures (check local codes for exact setbacks).

- Ensure surface drainage slopes away from the well to prevent pooling and runoff.

- Avoid driving or placing heavy equipment over the wellhead.

- Use corrosion-resistant materials where water chemistry is aggressive.

- Schedule regular pump servicing and annual water testing for bacteria and other key indicators.

Seasonal concerns: freezing and storms

Cold weather and storms create extra risks for casing and wellhead integrity.

- Frost and freezing can damage shallow piping and, in some cases, disturb shallow casings. Insulate above-ground components and bury pipes below frost depth when possible.

- After heavy storms or flooding, test your well immediately for bacterial contamination and turbidity. Surface water can infiltrate if the wellhead seal is compromised.

- Inspect the well after earthquakes or ground-shifting events for structural damage.

Permits, codes, and reporting

Local and state regulations may dictate well construction standards, repair practices, and reporting requirements. You should:

- Check local building and environmental health codes before any major well work.

- Use licensed well contractors for repairs requiring permits.

- Report contamination issues to your local health department if required—some jurisdictions mandate notification for positive bacterial tests or chemical contamination.

- Follow proper abandonment procedures if a well is out of service; improper abandonment creates hazards.

Choosing a qualified well professional

Finding the right contractor makes a big difference in diagnosis and repair. Consider these factors:

- Licensing: Verify state or provincial well contractor licenses.

- Experience: Look for contractors with relevant experience in your well type and local geology.

- References: Ask for local references and check online reviews.

- Inspection tools: Ensure they use downhole cameras, pressure testing, and proper water testing protocols.

- Warranties: Ask about warranties or guarantees for repairs.

- Written proposals: Get detailed estimates describing the scope, materials, timeline, and costs.

Safety considerations for inspections and repairs

Wells can be dangerous work sites. Make sure safety is prioritized.

- Avoid confined space entry unless performed by trained professionals with proper equipment.

- Electrically isolate pump and controls before any work.

- Prevent contamination: do not remove or open the well cap without protective protocols.

- Be cautious with disinfectants like chlorine—they must be used in correct concentrations and flushed properly.

When replacement is the best option

You may need a full re-drill when:

- Casing damage is widespread or deep and cannot be practically repaired.

- Contamination is persistent and originates from deep fissures or pathways not remediable by grouting.

- The well yield is severely reduced and repair costs approach or exceed replacement costs.

- Local rules require new construction to meet current standards and setbacks.

Replacement provides a long-term solution and modern materials for durability and sanitary protection.

Preventive maintenance schedule

Establish a routine to catch issues early and extend your well’s life.

- Annually: Test for total coliform and E. coli; visually inspect wellhead and cap.

- Every 2–3 years: Have a professional inspect the pump and electrical system.

- After major weather events: Test water quality and inspect for surface damage.

- Every 5–10 years: Consider professional downhole inspection if you notice any performance or water quality changes.

Keeping records of inspections, tests, and repairs helps track trends and supports decisions about repair vs replacement.

Common myths and misconceptions

- Myth: “Clear water is always safe.” Reality: Water can look clear and still have bacteria, nitrates, or VOCs. Testing is the only reliable assessment.

- Myth: “If the wellhead looks fine, the casing must be fine.” Reality: Many casing issues occur below ground and are not visible from the surface.

- Myth: “Any patchwork fixes are permanent.” Reality: Temporary repairs may buy time but not always solve underlying defects.

Practical checklist: what to do if you suspect a cracked casing

- Stop using water for drinking/cooking until you know it’s safe.

- Take photographs and notes of visible issues at the wellhead.

- Run basic DIY checks: flow, turbidity, odors, and visible damage.

- Collect water samples for bacterial testing immediately; test for nitrates and other likely contaminants if concerns exist.

- Contact a licensed well contractor for inspection and testing.

- Follow professional advice on repairs, relining, or replacement.

- Inform local health authorities if tests show contamination that could affect public health.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Can a small crack in casing really contaminate my water?

Yes. Even small cracks can allow surface water, bacteria, and chemicals to bypass sanitary seals and enter your water supply, especially during heavy rain or flooding.

Is a cracked casing visible from above ground?

Not always. You can see surface signs like a damaged cap or rust, but many cracks are below ground and require downhole inspection to detect.

How long does it take to repair a cracked casing?

Simple surface sealing or patching can be done in a day or two. Re-casing, lining, or drilling a new well can take days to weeks depending on permitting, depth, and complexity.

Is shock chlorination enough after a casing repair?

Shock chlorination disinfects the well but does not fix structural damage. It’s a vital step after many repairs but must be combined with proper repair or replacement if the casing is compromised.

Do homeowners’ insurance policies cover well casing damage?

Coverage varies widely. Check your policy and consult your insurer. Damage from certain perils may be covered, while wear-and-tear or maintenance issues typically are not.

Final thoughts and next steps

You can’t always see a cracked well casing, but you can watch for signs and act quickly. Prioritize water testing after any event that could allow surface runoff into the well, and keep records of test results and professional inspections. If you suspect damage, use alternate water sources and call a licensed well professional to diagnose and recommend repairs.

If you’d like, you can use the checklist below to get started. It will help you prepare for questions when you call a professional.

Quick homeowner checklist

- Stop using well water for drinking/cooking if you suspect contamination.

- Photograph and document visible wellhead issues.

- Test for total coliform and E. coli immediately.

- Check for turbidity, odor, and sediment.

- Turn off the pump only if advised by a professional.

- Call a licensed well contractor for inspection and testing.

- Follow up with recommended repairs and post-repair testing.

By paying attention to your well’s condition, maintaining routine checks, and acting promptly on signs of trouble, you protect your health, equipment, and property value. If you want, provide details about what you’re seeing at your well and I can help you prioritize next steps.