?Are you concerned about E. coli showing up in your well water and wondering what to do about disinfecting your well pump safely?

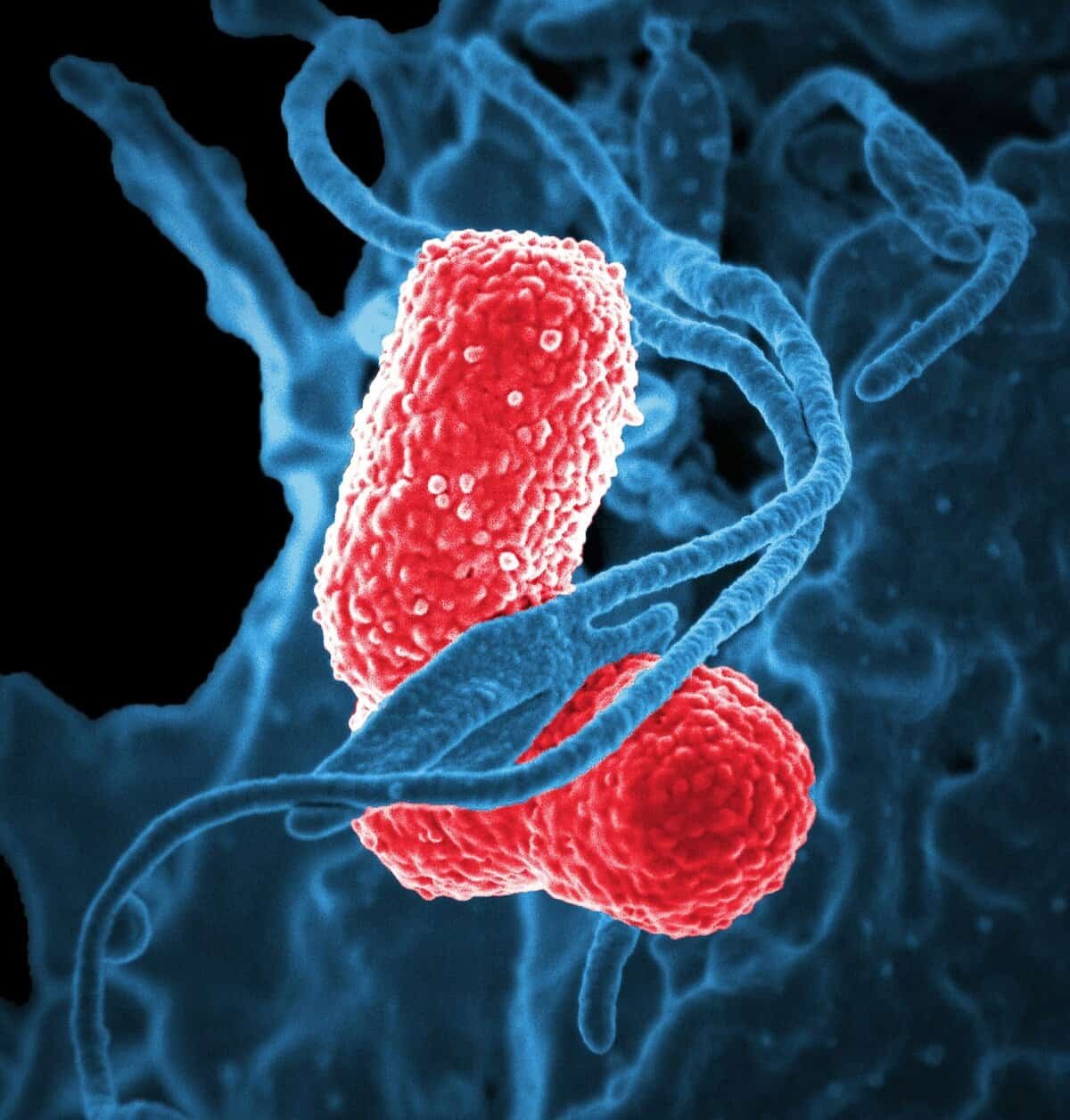

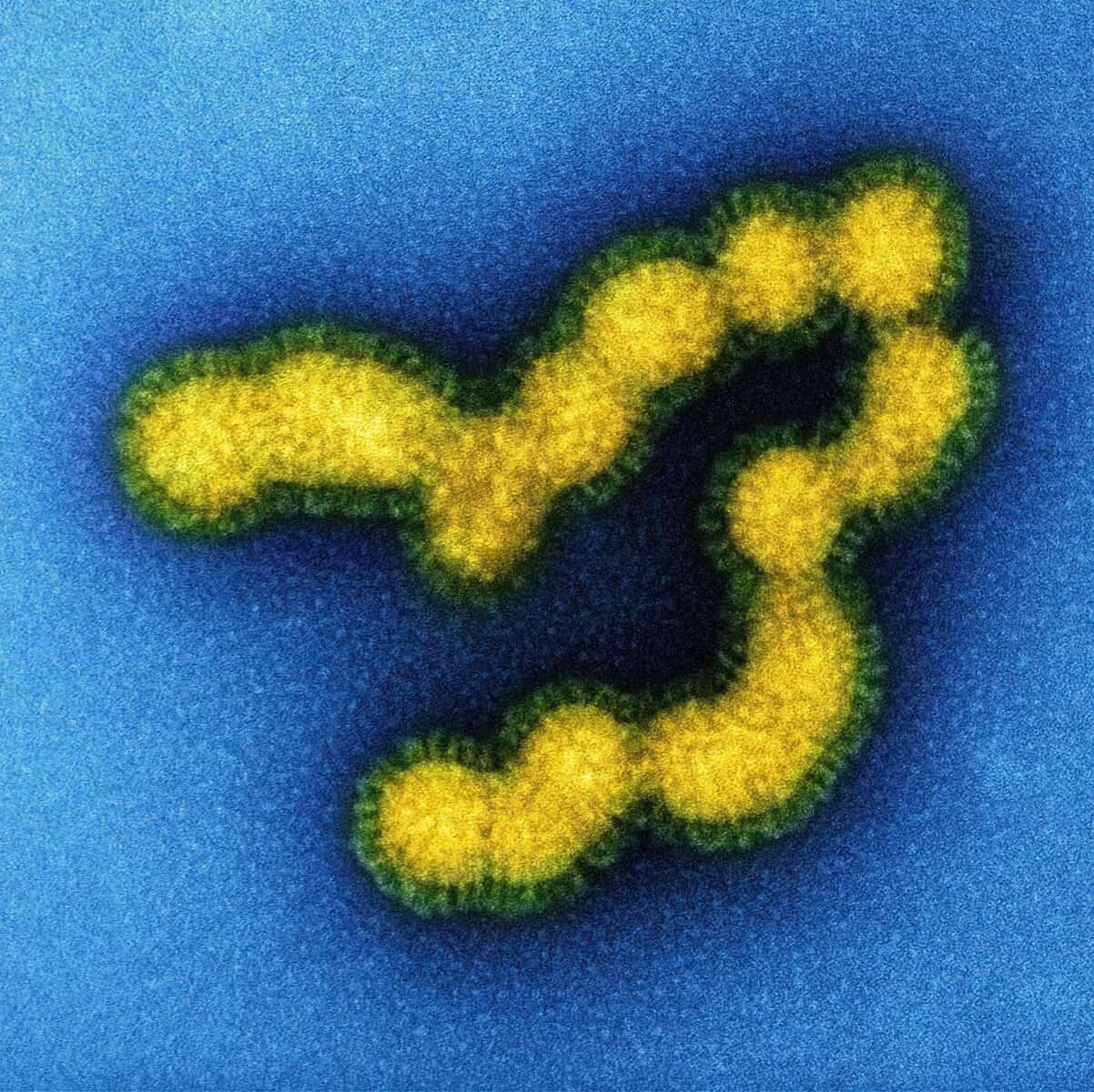

What is E. coli and why does it matter for your well?

E. coli (Escherichia coli) is a type of bacteria commonly found in the intestines of people and animals. Most strains are harmless, but some indicate fecal contamination and can cause illness. When E. coli is detected in your well water, it tells you that pathogens from fecal material may have entered the water supply and that action is needed to protect your health.

You should treat any E. coli detection seriously because it signals potential exposure to pathogens that can cause stomach illness, especially for children, elderly people, pregnant people, and anyone with a weakened immune system.

How does E. coli get into well water?

Contamination can occur through many routes. Understanding these helps you reduce risk and choose the right corrective actions.

You can get E. coli in your well water from:

- Surface runoff after heavy rains that carries animal or human waste into poorly sealed wells.

- Cracked or damaged well casings or caps that let surface water or insects inside.

- Nearby failing septic systems or sewage lines leaching into groundwater.

- Livestock or wildlife near the wellhead.

- Flooding events that overtop the wellhead or saturate the ground around it.

- Improperly located wells that are too close to sources of contamination.

How often should you test your well?

Testing frequency depends on your situation, but regular testing helps you catch contamination early.

You should:

- Test for total coliform and E. coli at least once a year.

- Test immediately after construction, repair, pump replacement, or flooding.

- Test more often (e.g., quarterly) if you have recurring problems, reactive household members, or agricultural activity nearby.

- Consider additional tests (nitrates, bacteria, metals) based on land use and local health guidance.

Immediate actions if a test shows E. coli

Take practical steps right away to reduce exposure and begin correction.

You should:

- Stop drinking the water and use bottled water or boiled water for drinking, cooking, and brushing teeth until the system is disinfected and tests clear.

- Avoid using the water for food preparation and for young children until safe water is confirmed.

- Contact your local health department for guidance and resources.

- Arrange to disinfect the well and plumbing (shock chlorination or professional disinfection) and retest after the recommended wait period.

Preventive measures to reduce E. coli risk (overview)

Prevention reduces the chance you’ll need to disinfect.

You should:

- Keep your wellhead secure: a sanitary well cap and intact casing are essential.

- Maintain setbacks: keep livestock, manure piles, septic systems, and chemical storage well away from the well.

- Grade the ground surface so water drains away from the well.

- Repair or replace cracked casings, loose caps, or broken seals immediately.

- Keep vegetation trimmed and avoid storing fuel, chemicals, or materials near the wellhead.

- Seal unused wells and decommission them according to local regulations.

Safe practices for disinfecting your well pump and well (overview)

Disinfecting a well and pump requires planning, the right materials, and care to avoid damaging equipment or harming yourself or the environment.

You should:

- Test first to confirm contamination and after disinfection to verify success.

- Follow a step-by-step shock chlorination procedure suited to your well type (shallow, deep, submersible pump, jet pump).

- Use unscented household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) for shock chlorination.

- Observe manufacturer recommendations for disinfecting pumps, pressure tanks, water softeners, and filtration systems; some devices should be bypassed or serviced by professionals.

- Consider hiring a licensed well contractor for submersible pump removal or if you are uncomfortable performing any part of the process.

Safety reminders before you begin

Chlorine is effective but can be hazardous if handled incorrectly.

You should:

- Wear chemical-resistant gloves and eye protection.

- Work in a ventilated area and avoid inhaling chlorine fumes.

- Never mix household bleach with ammonia or acids (this releases dangerous gases).

- Protect plants and septic systems from highly chlorinated water during flushing.

- Disconnect power to the pump and follow lockout/tagout procedures where applicable.

Choosing the right disinfection approach

There are two common ways to disinfect: shock chlorination (one-time high-concentration application) and continuous disinfection (ongoing low-level residual). The right choice depends on the problem.

You should choose:

- Shock chlorination for an acute bacterial contamination event (E. coli detection).

- Continuous chlorination or UV systems if you need long-term protection and frequent contamination.

- Professional solutions (commercial scale chlorination systems, UV with sensors, or properly maintained filtration) for recurring contamination or for whole-house treatment.

Step-by-step: How to shock-chlorinate a well (homeowner-friendly)

This is a commonly used method to treat wells contaminated with coliform bacteria or E. coli. If you’re not comfortable performing any step, call a licensed well professional.

You should follow these steps:

Gather supplies and prepare:

- Unscented household bleach (5–6% sodium hypochlorite).

- Clean buckets, a funnel, a measuring container.

- Rubber gloves and eye protection.

- A hose for flushing and a way to dispose of chlorinated water safely.

- A test kit or lab contact for follow-up water testing.

Calculate the well water volume:

- Determine well diameter and the depth to water.

- Use the formula or table below to estimate gallons of water in the well column.

- Add an estimate for water in the distribution lines if you’ll disinfect plumbing (usually add some extra gallons for pipes).

Choose target chlorine concentration:

- Typical shock concentrations: 50–200 ppm free chlorine throughout the well and distribution system.

- Many health departments recommend 50–100 ppm for routine shock chlorination; for severe contamination you might use higher concentrations up to about 200 ppm. Check your local health department for exact guidance.

Add bleach:

- Turn off the pump at the breaker and the pressure switch.

- Remove the well cap or seal (if present). If the cap is damaged, replace it after chlorinating.

- Pour the calculated amount of bleach into the well. If the well pump is submersible, do NOT remove the pump unless you are a trained pump technician. For submersible pumps, pour the bleach down the well casing or introduce it via the pump following manufacturer guidance.

- Mix with some clean water in a bucket and pour to help distribute the bleach.

Circulate to treat the distribution system:

- Turn the pump back on and open each faucet, one at a time, starting with outside faucets, until you smell chlorine. Then close the faucet. This ensures the chlorinated water reaches all parts of the distribution system, including the pressure tank and lines.

- Don’t forget to run water at outside spigots and washing machine taps; bypass or protect any devices that can be damaged by chlorine.

Let it sit:

- Close all taps and let the chlorinated water sit for at least 6–12 hours; many recommend 12–24 hours for better efficacy. Avoid using water during this time.

Flush and neutralize:

- Open outside faucets first and run until the chlorine smell is gone. Then move indoors, opening taps and flushing toilets until the chlorine odor is no longer noticeable.

- Be cautious about sending strongly chlorinated water into septic systems or onto plant beds. If necessary, neutralize with sodium thiosulfate before discharging to sensitive areas (follow product instructions and local regulations).

Retest the water:

- Wait 7–10 days after flushing and then collect a sample for total coliform and E. coli testing from a tap used for drinking water. Your local health department or certified lab can advise on sampling technique and timing.

- If test results are still positive, repeat disinfection and contact local health authorities or a well professional.

Table: Gallons per foot of water in common well diameters

This table helps you estimate the volume of water in your well column so you can compute bleach needs.

| Well diameter | Gallons per foot of water |

|---|---|

| 4 inches | 0.65 gal/ft |

| 6 inches | 1.47 gal/ft |

| 8 inches | 2.61 gal/ft |

| 10 inches | 4.08 gal/ft |

| 12 inches | 5.87 gal/ft |

Use the value for your well diameter and multiply by the depth of water to get total gallons in the well column.

How to calculate how much household bleach to use

You can calculate bleach volume using this method if you want precise dosing.

You should:

- Estimate total gallons (G) of water in the well column: G = gallons per foot × water depth (ft).

- Decide target ppm of free chlorine (e.g., 50–100 ppm).

- Use this quick formula for bleach volume in ounces (assuming 5.25–6% household bleach):

- Bleach (oz) ≈ 0.00244 × ppm × G

- Convert ounces to cups (8 oz = 1 cup) or liters as needed.

Example table for a 6-inch well (1.47 gal/ft) with common water depths:

| Water depth (ft) | Gallons (approx) | Bleach for 50 ppm (approx cups) | Bleach for 200 ppm (approx cups) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 ft | 36.8 gal | 1.12 cups | 4.47 cups |

| 50 ft | 73.4 gal | 2.24 cups | 8.95 cups |

| 100 ft | 146.8 gal | 4.47 cups | 17.9 cups (~1.12 qt for 200 ppm) |

| 200 ft | 293.6 gal | 8.95 cups (~0.56 gal) | 35.8 cups (~2.24 gal) |

Note: These are approximate values based on 5–6% household bleach and assume you want the specified ppm uniformly throughout the well water column. You will often need additional bleach to disinfect distribution plumbing and pressure tanks. When in doubt, consult your local health authority or a well professional.

Special considerations for submersible pumps and equipment

Submersible pumps are common but more sensitive to improper handling.

You should:

- Not remove or service a submersible pump unless you are trained or hire a pump contractor. Removing a submersible pump improperly can damage it and may void warranties.

- If a pump has biological growth or smells, discuss options with a pump technician: sometimes the pump will be pulled, sanitized, and reinstalled after shock chlorination.

- Be cautious about introducing concentrated bleach directly into the pump motor or seals—follow the pump manufacturer’s instructions.

- Bypass or remove water treatment devices (carbon filters, water softeners, UV systems) during shock chlorination. Carbon removes chlorine and may be a place where bacteria can survive; it often needs replacement or professional sanitizing if contaminated.

How to disinfect pressure tanks, filters, and household plumbing

Your plumbing system can harbor bacteria; disinfecting the well without treating plumbing can let contamination persist.

You should:

- After introducing bleach to the well and circulating it, ensure chlorinated water has reached every faucet and appliance (washing machine, dishwasher).

- Bypass devices that could be damaged by chlorine (water softeners, certain filters). After the process, follow manufacturer procedures for disinfecting or regenerating these devices.

- Replace disposable filters (sediment/carbon) after shock chlorination because they may trap bacteria.

- Consider professional cleaning for pressure tanks that are not designed to withstand concentrated chlorine—they may require different methods or replacement.

Continuous disinfection and long-term strategies

If you face persistent contamination, a single shock may not be enough.

You should consider:

- Continuous chlorination systems that inject a controlled amount of chlorine to maintain a low residual (commonly 0.2–2.0 ppm) for ongoing protection.

- UV disinfection at point-of-entry (POE) or point-of-use (POU) systems for reliable inactivation of bacteria, combined with prefiltration.

- Periodic maintenance and monitoring: change filters, check UV lamp life, and test water regularly.

- Address the contamination source (septic repairs, sealing well) to avoid reliance purely on treatment.

Environmental and disposal concerns

Chlorinated water can harm plants, septic systems, and aquatic life.

You should:

- Avoid disposing of highly chlorinated water directly onto vegetable gardens, lawns, or into streams and ponds.

- When flushing chlorinated water, direct it to a sanitary sewer if allowed, or onto a hard surface where it can dissipate and volatilize away from plants and sensitive areas.

- Neutralize residual chlorine with sodium thiosulfate before discharging into septic systems or near vegetation, following product guidance.

- Check local regulations for disposal rules in your area.

Troubleshooting common problems

If disinfection doesn’t work or problems recur, diagnose methodically.

You should:

- Retest after disinfection. If positive results persist, the problem may be structural (cracked casing) or ongoing (septic leak).

- Inspect the wellhead, cap, casing, and surrounding area for defects or pathways for surface water entry.

- Consider hydrogeological factors: shallow water tables and high groundwater fluctuation can increase contamination risk.

- Replace corroded well components and install an approved watertight sanitary seal or cap.

- Consult a licensed well contractor or your local health department for persistent or unexplained contamination.

When to call a professional

Certain situations warrant professional assistance.

You should hire a pro if:

- You have a submersible pump problem and the pump must be pulled.

- The well casing is cracked, the cap is missing, or the wellhead is damaged.

- You cannot locate the contamination source or contamination recurs after repeated disinfecting.

- You need a continuous disinfection system, advanced filtration, or a POE system sized and installed professionally.

- Local regulations require licensed work for well repairs or new installations.

Table: Common contamination sources and practical prevention actions

This table helps you match problems with prevention steps.

| Source of contamination | Prevention and corrective action |

|---|---|

| Surface runoff and floods | Grade ground away from well; install watertight sanitary cap; seal flows |

| Nearby septic system failure | Inspect and pump septic; maintain setback distances; repair leaks |

| Livestock or manure storage | Keep animals and manure downhill and distant from the well |

| Cracked casing or loose cap | Repair/replace casing and install a secure, sanitary well cap |

| Flooding events | Test after flood; disinfect well and plumbing if contaminated |

| Wildlife/insect entry | Use screened vents and approved caps; seal openings |

| Old or abandoned wells nearby | Properly decommission unused wells per regulations |

After disinfection: monitoring and record-keeping

Keeping records helps you track problems and responses.

You should:

- Keep lab results, dates of disinfection, amounts and types of chemicals used, and equipment service records.

- Create a schedule for routine testing and maintenance tasks (caps, seals, pressure tank checks).

- Share results or concerns with your local health department or state well program if contamination persists.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

These succinct answers address common homeowner concerns.

Q: Can I boil water instead of disinfecting the well? A: Boiling is a short-term solution for making water safe to drink, but it does not remove the source of contamination. You still need to disinfect and fix the well to ensure long-term safety.

Q: Is bottled water the only safe option after E. coli is found? A: Bottled water is a safe interim option. You can also boil water for at least one minute (longer at high altitude) for drinking and cooking until the well is disinfected and tests clear.

Q: How long until my water is safe after shock chlorination? A: After shock chlorination and thorough flushing, retest in 7–10 days. If tests show no E. coli and only acceptable total coliform results, you can resume normal use.

Q: Will chlorine affect my well pump or plumbing? A: High concentrations of chlorine can harm rubber components, some metals, and certain filters. Bypass or protect devices and consult manufacturers or a pro for guidance.

Q: Can I use pool chlorinator or calcium hypochlorite instead of household bleach? A: Yes, some professionals use other chlorine sources, but dosing differs and handling can be more hazardous. If you use products other than household bleach, follow professional guidance and safety protocols.

Final checklist before you start disinfecting

Use this checklist to prepare and protect yourself and your system.

You should confirm:

- You have unscented household bleach (5–6%) and PPE.

- You know your well diameter and static water depth to calculate bleach dosage.

- The pump power can be safely turned off and on; you know how to bypass treatment devices.

- You have a plan to flush/or neutralize and dispose of chlorinated water safely.

- You will retest water after chlorination and keep records of actions taken.

Where to get help and more information

If you need assistance, look to local authorities and professionals.

You should contact:

- Your local or state health department for testing resources and local guidance.

- A licensed well contractor or water treatment professional for pump removal, extensive repairs, or installation of continuous disinfection systems.

- Certified laboratories for reliable bacteriological testing.

By following these recommendations, you’ll greatly reduce your risk of E. coli contamination, perform safe and effective shock chlorination when needed, and maintain a safer well system over time. If contamination persists after you’ve taken careful steps, engage a qualified professional and your local health agency to diagnose and fix underlying problems.