Are you concerned that E. coli might be contaminating your well water and wondering what you should do right now?

How Do I Prevent E. Coli In My Well Water?

You rely on your well for safe drinking water, cooking, and household use, so preventing E. coli contamination is essential. This article walks you through what E. coli is, how contamination happens, how to test, and both everyday preventive measures and safe disinfection practices — including step-by-step guidance for shock chlorinating a well and treating a well pump.

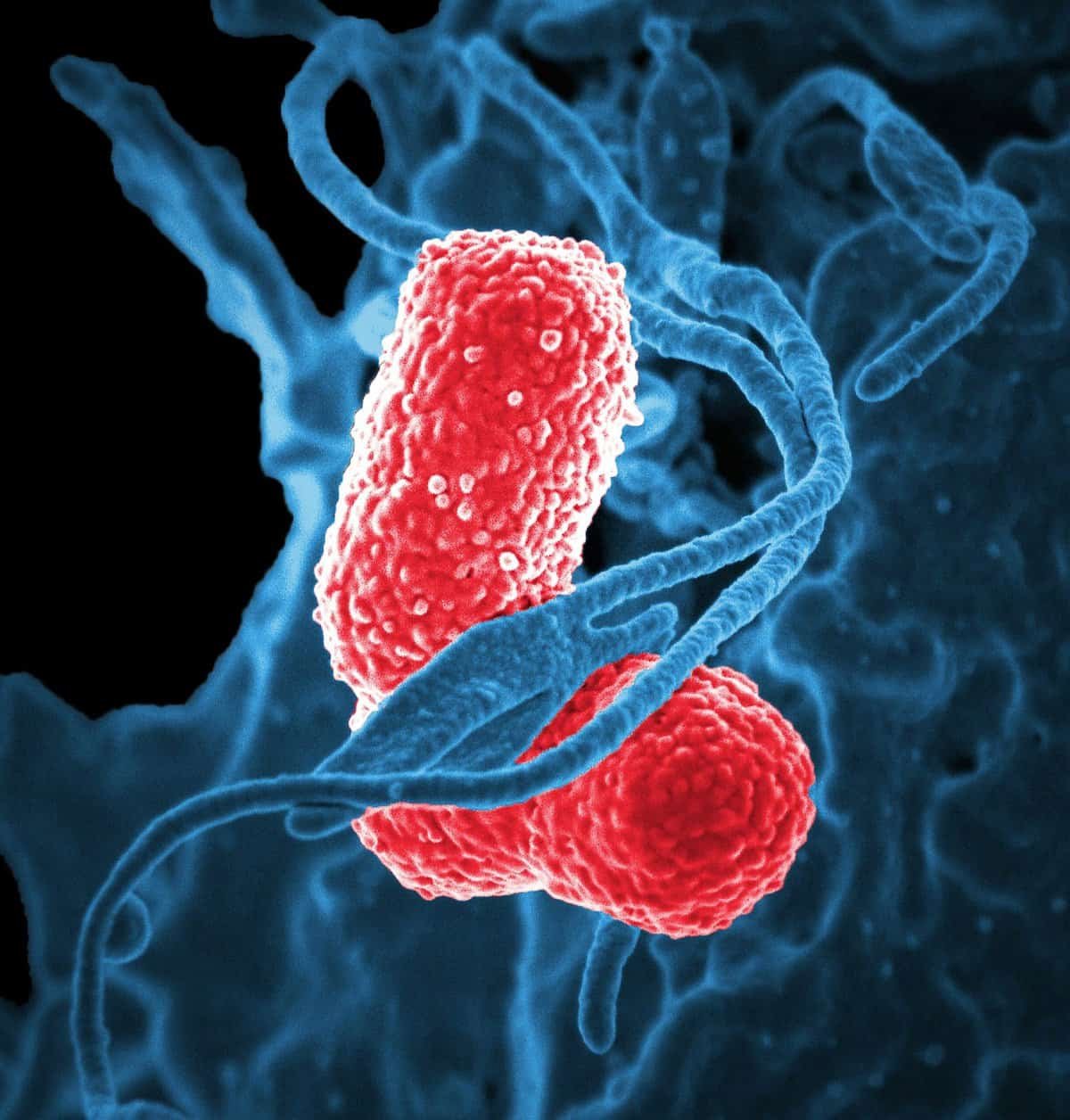

What is E. coli and why should you care?

E. coli (Escherichia coli) is a group of bacteria commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals. While many strains are harmless, some can cause severe gastrointestinal illness. If E. coli is present in your well water, it indicates fecal contamination and a possible pathway for other pathogens. You shouldn’t drink, cook, or brush your teeth with water that tests positive for E. coli until you’ve corrected the contamination and confirmed the water is safe.

How E. coli gets into wells

Understanding likely contamination routes helps you address the problem at the source. E. coli usually enters well water through:

- Surface runoff after heavy rain or flooding that carries animal or human waste.

- Faulty or damaged well casing, cap, or grout that allows surface water to enter.

- Nearby failing septic systems or sewer leaks.

- Animal activity close to the well (livestock, wildlife).

- Contaminated water that entered during well construction, repair, or pump work.

- Poorly sealed or abandoned wells nearby.

Take action quickly if any of these conditions apply after storms, installation work, or changes in your property.

Typical signs of contamination

You often won’t see E. coli, but these signs suggest potential problems:

- Cloudy, foul-smelling, or discolored water

- Sudden change in water taste

- Illness among household members (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting)

- Recently flooded well area or visible well damage

If you notice any of these, test the water immediately.

Testing your well for E. coli and other bacteria

You need lab-confirmed results to know whether your well water is contaminated.

- Test frequency: Test for total coliforms and E. coli at least once a year. Test immediately after well construction, repairs, pump work, or flooding, and if anyone in the household gets a gastrointestinal illness.

- How to test: Use a certified laboratory or your local health department. They can provide sterile sample bottles and instructions. Follow sampling instructions closely to avoid contamination of the sample.

- What the results mean: If E. coli is detected, treat the water as contaminated. If only total coliforms are present without E. coli, you have a potential vulnerability and should investigate and retest.

Never drink water from a well that tests positive for E. coli until you’ve disinfected and confirmed the water is clean.

Immediate steps if your well tests positive

If E. coli appears in your test results, take these immediate actions:

- Stop drinking the water. Use bottled water or boiled water (boil for 1 minute at sea level, 3 minutes at high elevations) for drinking, cooking, brushing teeth, and preparing infant formula until the well is disinfected and test results are clear.

- Notify local health authorities for guidance and testing resources.

- Arrange for disinfection of the well (shock chlorination) — either DIY if you’re comfortable, or hire a licensed well contractor.

- Test again after disinfection to confirm the water is free of E. coli.

Long-term prevention: site, construction, and maintenance

Prevention focuses on keeping surface water and contamination sources away from the well and ensuring the well is properly built and maintained.

Well head protection and construction

You should make sure:

- The well casing extends above ground, and the area around the casing is sloped so water runs away.

- The well cap is sanitary, intact, and securely fastened.

- The well is properly grouted/sealed where the casing enters the ground.

- Abandoned wells on your property are properly plugged by a professional.

You’ll reduce contamination risk dramatically if the well is properly constructed and sealed.

Surface drainage and landscaping

Simple changes around your well can help:

- Grade the ground around the well so surface water flows away from the casing.

- Maintain a 10–15 foot clear, well-drained zone around the well; avoid storing fuel, chemicals, or manure nearby.

- Plant grass or other ground cover to reduce erosion, but avoid planting deep-rooted species too close.

Septic system care and setbacks

Your septic system should be maintained and located at a safe distance from the well:

- Pump your septic tank on schedule (typically every 3–5 years) and repair any failures.

- Maintain setbacks: local codes vary, but often maintain at least 50–100 feet between well and septic components.

- Avoid altering soil or redirecting effluent in ways that could channel contaminants toward the well.

Animal control and fencing

Keep animals away from the well:

- Install fencing or barriers to keep livestock and pets from near the well head.

- Avoid storing manure up-slope from the well.

Routine maintenance and record-keeping

- Test annually for total coliforms and E. coli.

- Check well caps and casings periodically for damage.

- Keep records of tests, repairs, pump services, and any disinfection events.

Water-treatment options to protect against pathogens

Even with preventive measures, local geology or persistent contamination may require point-of-entry or point-of-use treatment.

Common treatment methods

- Shock chlorination: good for addressing bacterial contamination and emergency disinfection.

- Continuous chlorination: a feeder system can maintain a low residual disinfectant if contamination risk is ongoing (requires monitoring and corrosion management).

- Ultraviolet (UV) disinfection: effective for bacteria and viruses if water is clear (turbidity must be low).

- Filtration: sediment filtration protects UV systems and other disinfectants. Granular activated carbon or other filters can address taste/odor and some chemicals.

- Reverse osmosis (RO): effective at point-of-use for a small amount of drinking water; it removes many pathogens when properly maintained.

Select a system based on test results, flow requirements, water chemistry, and professional recommendations.

Combining treatments

Often you’ll pair methods — e.g., sediment filter + UV at point-of-entry, or continuous chlorine with a carbon filter at point-of-use for taste. Use certified equipment and maintain it regularly.

Safe practices for disinfecting a well pump and system

Whether you have a shallow well with a jet pump or a deep well with a submersible pump, disinfection should be done carefully to avoid damage or hazards. Below are general safe practices and a detailed shock chlorination method.

General safety and preparation

- Use unscented household bleach (sodium hypochlorite) without additives; 5–6% is common. Do not use scented or thickened formulations.

- Turn off electric power to the pump before working on electrical components or removing a pump.

- Wear gloves, eye protection, and protective clothing when handling chlorine.

- Keep children and pets away from the well and chlorinated water.

- Follow local regulations and manufacturer guidance, especially for pressure tanks and certain pump types.

When to call a professional

Hire a licensed well contractor or pump technician if:

- You need to remove or repair the pump.

- Your well is deeper than you’re comfortable calculating or accessing.

- The well configuration is unusual or the pump control equipment is complex.

- Repeated contamination indicates structural problems with the well.

Professionals have tools to inspect well integrity (camera inspection), measure well yield, and treat pumps and tanks safely.

Step-by-step shock chlorination (standard DIY approach)

Shock chlorination is intended to eliminate bacteria from the well, pump, pressure tank, and plumbing. Use this method for a contaminated well that’s structurally sound.

Note: The sample calculations and volumes below assume common household bleach around 5.25% sodium hypochlorite. Adjust if your product has different concentration.

Overview of steps

- Calculate the volume of water in the well bore and plumbing you’ll disinfect.

- Determine the amount of bleach required to reach a target free chlorine concentration (commonly 50–100 mg/L or “ppm” for shock treatment).

- Turn off the pump power.

- Remove the well cap and add the calculated bleach to the well; also pour some bleach into a bucket of water to wash the casing and disinfect the cap.

- Re-secure the well cap.

- Connect a hose to an interior faucet and run water back into the well until you smell chlorine at the well; this circulates chlorine through the pump and plumbing.

- Let the system sit for at least 12–24 hours (24 hours preferred).

- After waiting, run each tap until chlorine smell is gone and flush the system thoroughly.

- After flushing, test for total coliforms and E. coli to confirm disinfection.

Calculating bleach dosage

You must figure the water volume to determine how much bleach to use.

- Volume of water in the well (gallons) = depth of water column (feet) × cross-sectional area of casing (ft²) × 7.48 gallons/ft³.

- Cross-sectional area of casing = π × (diameter in feet / 2)^2.

A simpler route: use the following table for quick estimates of the well bore volume (gallons per foot):

| Well casing diameter | Gallons per foot (approx.) |

|---|---|

| 4 inches | 0.65 |

| 5 inches | 1.01 |

| 6 inches | 1.44 |

| 8 inches | 2.55 |

| 10 inches | 3.99 |

To estimate total gallons in the well bore:

- Multiply gallons per foot by the depth of the water column (distance from water level to bottom of well). Then add approximate household plumbing/pump/pressure tank storage (common conservative addition is 10–20 gallons for small systems, or calculate actual tank volume if known).

To estimate bleach quantity for a target chlorine concentration:

- Use the approximate formula: mL of 5.25% bleach ≈ C (ppm) × total gallons × 0.07214

- For example, to reach 50 ppm:

- mL bleach = 50 × total gallons × 0.07214 ≈ 3.607 × total gallons

- For 100 gallons, that’s about 360 mL (a little over 1.5 cups)

Helpful dosage table (approximate amounts of 5.25% bleach)

| Total water volume (gallons) | Bleach for 50 ppm | Bleach for 100 ppm |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 180 mL (¾ cup) | 360 mL (1.5 cups) |

| 100 | 360 mL (1.5 cups) | 720 mL (3 cups) |

| 500 | 1.8 L (7.5 cups) | 3.6 L (15 cups) |

| 1,000 | 3.6 L (15 cups) | 7.2 L (30 cups) |

Note: 1 cup ≈ 236 mL. Adjust for the actual concentration of your bleach product.

Detailed shock chlorination procedure

- Measure or estimate the water volume to get the bleach dose (see calculation above).

- Turn off power to the pump at the breaker or switch.

- Remove the well cap carefully and inspect for damage. If the cap is damaged, replace it before re-sealing the well.

- Pour the calculated amount of unscented bleach directly into the well. To help wash down the casing, pour an additional cup or two of bleach into a bucket of water and pour or spray it down the casing to disinfect the cap and casing top.

- Replace the well cap but do not secure it completely if the cap needs to vent — follow the cap design and local guidance.

- Turn the pump circuit back on. Open an outside faucet and run water into the well (or use an interior faucet) to circulate chlorinated water through the pump, pressure tank, and pipes. Run until you can smell chlorine at the faucet that’s circulating back. This step ensures the pump, pressure tank, and household plumbing are exposed.

- After you smell chlorine returning to the well area or well head, turn off the circulating faucet and allow the system to sit for at least 12 hours; 24 hours gives a stronger kill. Do not use the water during this period.

- After contact time has elapsed, open an outside hose bib or faucet and flush the system by running water until chlorine smell is gone. Then go inside and run every faucet (hot and cold) and flush toilets until the chlorine taste and smell disappear. Make sure any water used for plants, livestock, or septic systems is decanted or diluted appropriately — do not discharge highly chlorinated water into sensitive environments without dilution.

- If you have a water softener or treatment systems, isolate or bypass them during chlorination and flush them afterward per manufacturer instructions.

- Collect and submit a water sample to a certified lab for total coliforms and E. coli after the system has been flushed and water is clear — usually 1–2 days after flushing (follow the local lab’s guidance on sample timing).

After disinfection: testing and follow-up

- If test results are negative for E. coli and total coliform, you can return to normal use.

- If tests remain positive, repeat shock chlorination or contact a well professional. Persistent contamination often indicates structural problems or a nearby contamination source that requires correction.

- Keep records of each disinfection, bleach amounts used, and test results.

Specific safe practices when disinfecting the well pump and related equipment

The pump and pressure tank are important parts of the system; treat them with care.

Submersible pumps

- Do not attempt to remove or service a submersible pump unless you have expertise. If you must remove it, hire a professional.

- When disinfecting in place, circulate chlorinated water through the pump. This should disinfect the pump housing, but it does not sterilize internal motor windings. Properly mixed chlorine at shock concentrations is generally safe for brief exposure.

- Avoid running the pump dry. If you must run it to circulate water, ensure water level is adequate.

Jet pumps and above-ground pumps

- Turn off electrical power before working on the pump.

- Disinfect the suction line and pump housing by running chlorinated water through the system.

- If you remove the pump for servicing, soak and rinse external pump components in a sanitizing solution (100–200 ppm chlorine) and allow to dry before reinstallation.

Pressure tanks

- If you have a single-unit pressure tank, treat the piping and water in the tank during circulation.

- If your pressure tank has an internal bladder, check the manufacturer’s recommendations — prolonged exposure to concentrated chlorine can sometimes affect bladder materials. Usually, circulating chlorinated water through the tank is acceptable for short periods, but if unsure, consult the manufacturer or a professional.

- For older steel tanks, check for corrosion before and after chlorination and be mindful of potential chemical reactions.

Electrical and safety concerns

- Shut off all associated electrical circuits before working on pumps, controls, or pressure switches.

- Never introduce bleach near open flames or sparks; it is not flammable but can generate hazardous vapors with other chemicals.

- Dispose of excess chlorinated flush water safely and in accordance with local guidance — avoid pouring large volumes into septic systems or sensitive ecosystems without dilution.

Preventing recontamination and recurring problems

If you disinfected once but contamination returns, take these steps:

- Inspect for structural defects: cracked casing, damaged sanitary seal, or missing grout can let surface water in.

- Check for persistent nearby contamination sources: septic failure, livestock grazing, or poorly sealed abandoned wells.

- Consider installing continuous disinfection (chlorine feed system) or a point-of-entry UV disinfecting system combined with pre-filtration if contamination is intermittent and sources cannot be entirely removed.

- Use routine monitoring: test quarterly if you have recurring problems until they’re resolved.

Quick reference: dos and don’ts

| Do | Don’t |

|---|---|

| Test well annually and after storms, repairs, or illness | Drink water that hasn’t been tested after a positive E. coli result |

| Use unscented household bleach for shock chlorination | Use scented or specialty bleaches with additives |

| Circulate chlorinated water through the pump and plumbing | Run pumps dry or attempt complex pump repairs without turning off power |

| Keep animals and waste away from the wellhead | Store fuel, manure, or chemicals near the well |

| Call a professional for pump removal, deep wells, or persistent contamination | Ignore repeated positive test results |

When to call local health or regulatory authorities

- If multiple people have symptoms of gastrointestinal illness that may be linked to the water.

- If you have persistent positive E. coli results despite treatment.

- If storm flooding inundated the wellhead.

- For advice on sample labs, local code requirements, or if you suspect a larger community contamination issue.

Final checklist before you consider the problem solved

- You’ve corrected any structural defects (casing, cap, grout) and removed contamination sources.

- You disinfected the well and plumbing per recommended procedure.

- You flushed the system until chlorine is gone (no strong chlorine taste).

- A certified lab reports negative results for E. coli and total coliforms after treatment.

- You’ve documented the event and set up a monitoring plan (test annually or more often if needed).

Closing recommendations

You can protect your household by combining preventative actions (good well construction, site management, septic maintenance) with regular testing and careful disinfection when needed. For routine shock chlorination, follow the calculation methods and safety steps shown here, but don’t hesitate to contact a licensed well contractor when the situation is complex or you’re unsure. If you maintain records, inspect the well regularly, and test your water as recommended, you’ll greatly reduce the chance of E. coli returning and keep your water supply safe.

If you want, I can help you calculate a bleach dose for your specific well dimensions (just provide casing diameter, water column depth, and whether you have a separate pressure tank volume).