Wondering how deep your residential water well should be and what factors determine the best depth for your home?

How Deep Should A Residential Water Well Be?

Choosing the right well depth is one of the most important decisions you’ll make when installing or repairing a residential water well. The depth affects water quantity, quality, cost, pump selection, long-term reliability, and maintenance. In this article you’ll get practical guidance on typical depth ranges, geological factors, testing and design considerations, cost estimates, and how to choose the right well contractor.

Why Well Depth Matters

Well depth influences the volume of water you can pump, the stability of supply during dry periods, and the types of contaminants you might encounter. A shallow well may be inexpensive to drill but could run dry in drought or be vulnerable to surface contaminants. A deeper well generally provides more stable supplies and different water chemistry, but it costs more upfront and requires different equipment.

You’ll need to balance cost, risk, and expected water demand when choosing the well depth.

Basic Types of Residential Wells and Typical Depths

Different well types are common around homes. Each type has typical depth ranges and installation methods that affect performance.

Dug Wells (Hand-excavated)

Dug wells are shallow, typically 10–30 feet deep. They’re wider in diameter and often lined with stone or concrete.

- Pros: Low-tech, low-cost initially.

- Cons: Very vulnerable to surface contamination and seasonal fluctuation.

Driven Wells

Driven wells use a drive point and are usually 15–50 feet deep in unconsolidated material like sand or gravel.

- Pros: Quick and inexpensive in suitable soils.

- Cons: Limited depth and yield; not suitable in fractured bedrock.

Drilled Wells (Rotary or Cable Tool)

Drilled wells range from 50 to several hundred feet, depending on geology. Typical residential drilled wells fall between 100 and 500 feet in many regions.

- Pros: Can access deep aquifers, higher yields, more reliable.

- Cons: Higher cost, requires professional drilling rigs.

Typical Depth Table

| Well Type | Typical Depth Range (feet) | Common Settings |

|---|---|---|

| Dug | 10–30 | High water table, rural properties |

| Driven | 15–50 | Sandy, unconsolidated soils |

| Drilled (shallow) | 50–150 | Sand/gravel aquifers, shallow bedrock |

| Drilled (deep) | 150–500+ | Fractured bedrock, deep confined aquifers |

These are typical ranges; local geologic conditions often dictate the actual depth required.

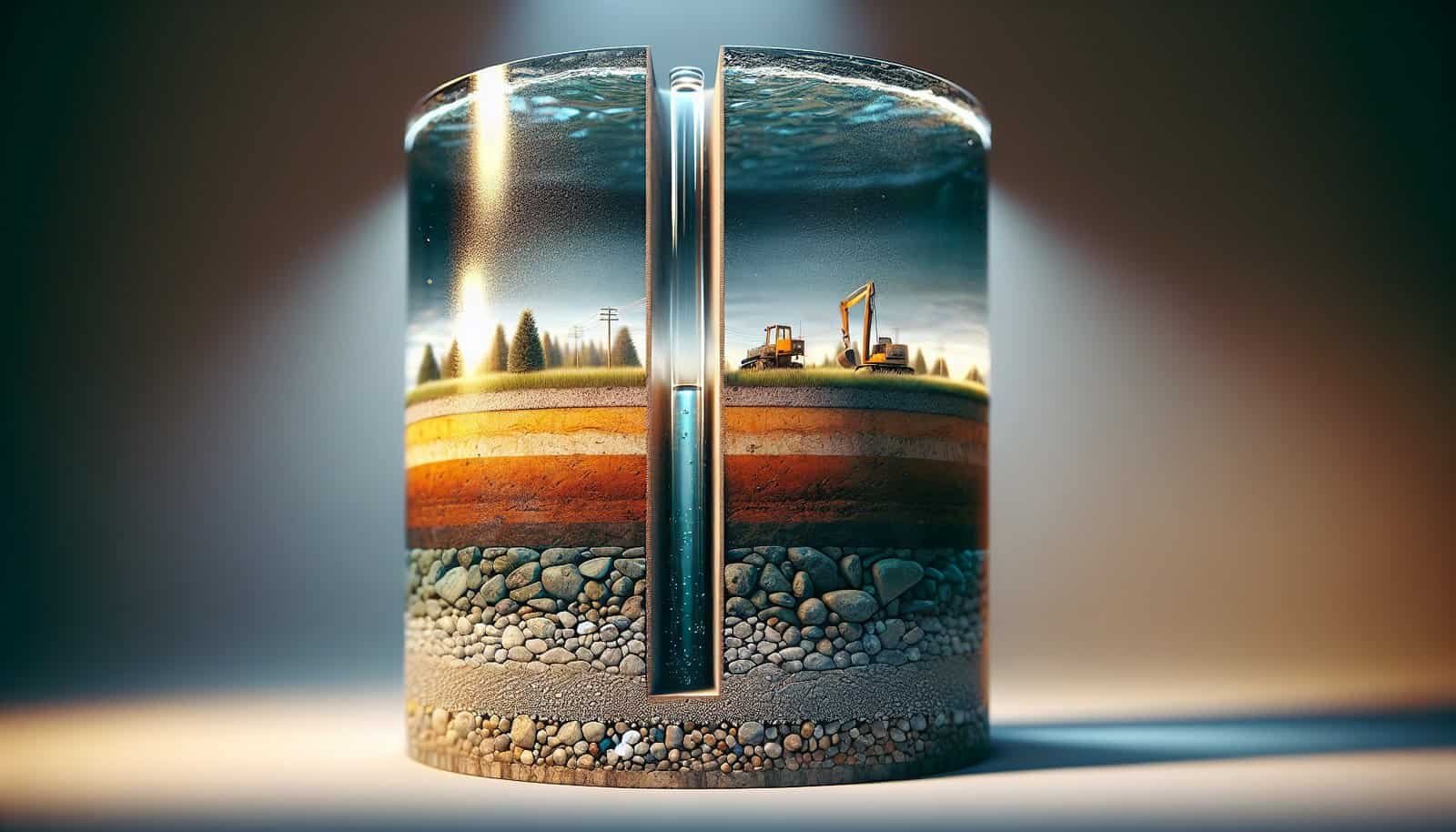

Geological Factors That Determine Well Depth

Understanding the subsurface geology at your site is crucial. The type of aquifer and local rock or soil layers determine how deep you must drill for an adequate supply.

Unconsolidated Aquifers (Sand, Gravel, Alluvium)

These aquifers typically sit near the surface and may produce good yields at shallow depths. However, they are more susceptible to contamination and seasonal changes in water level.

- Typical depth: 30–150 feet, depending on local sediment thickness.

Fractured Bedrock (Granite, Schist)

Water is stored and flows through fractures. You must intersect productive fractures, so depth can vary widely.

- Typical depth: 100–500+ feet; success depends on hitting fractured zones.

Karst Limestone and Dolomite

These aquifers can have productive cavities and conduits that yield large amounts of water, sometimes at shallower depths.

- Typical depth: 50–300 feet, but variability is high.

Glacial Deposits and Till

These mixed deposits can yield water in sand/gravel lenses interbedded with low-permeability till.

- Typical depth: highly variable; often requires drilling to find sand lenses.

Regional Variability

Your region’s hydrogeology is a major influence. For example:

- Coastal plain with shallow sediments: wells are often shallow (50–200 feet).

- Mountainous fractured rock: wells frequently must be deeper (200–1,000+ feet).

- Areas with perched water tables: shallow wells may work seasonally but can fail in dry periods.

Consulting local well logs and geological maps helps estimate typical depths in your area.

How Water Quality Changes with Depth

Water chemistry often changes with depth. Knowing likely contaminants helps you plan treatment when needed.

Common Trends

- Shallow wells: higher risk of bacterial contamination, nitrates from agricultural or septic sources, and organic matter.

- Intermediate depths: may have moderate hardness, iron, manganese.

- Very deep wells: can contain elevated dissolved salts, radon, arsenic, or other geogenic contaminants depending on geology.

Contaminants by Depth Table

| Contaminant | More Likely in Shallow Wells | More Likely in Deep Wells | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (E. coli) | Yes | Less common | Often from surface or septic systems |

| Nitrates | Yes (agriculture, septic) | Rare | Health risk for infants |

| Iron/Manganese | Moderate | Moderate to high | Causes staining and taste issues |

| Hardness (Ca/Mg) | Variable | Often higher | Causes scale; treatment available |

| Arsenic | Rare | Possible (geologic source) | Region-dependent |

| Radon | Rare | Possible in deep wells | Inhalation risk via indoor water use |

| Salinity/TDS | Typically lower | Can be higher | Deep saline aquifers in some regions |

Always test your well water after installation and at least annually for bacteria and other locally relevant parameters.

Yield and Pumping: Depth, Drawdown, and Specific Capacity

Well depth ties directly into yield—how much water you can pump sustainably.

Static Water Level vs. Pumped Water Level

- Static water level: water level when well is idle.

- Pumped water level: water level while pumping.

- Drawdown: difference between static and pumped levels; the well must be deep enough so the pump intake remains submerged during pumping.

You’ll want sufficient “freeboard” — the distance from the pump intake to the well bottom — and enough saturated length across the screen to maintain yield.

Specific Capacity

Specific capacity is yield (gallons per minute, gpm) divided by drawdown (ft). It tells you how productive a well is.

- Example: 10 gpm with 10 ft drawdown → specific capacity = 1 gpm/ft.

- Low specific capacity often means a need for deeper drilling or well rehabilitation.

Pump Selection

- Shallow wells often use jet pumps or shallow submersibles with limited lift.

- Deep wells require deep-set submersible pumps or turbine pumps, suitable for the drawdown and required flow.

Your contractor will recommend pump type and placement based on depth and expected drawdown.

How Seasonal and Drought Conditions Affect Depth Decisions

Water tables fluctuate. If your area has seasonal high and low water tables or recurring droughts, you’ll likely need a deeper well to ensure year-round supply.

- In areas with large seasonal change: plan for the lowest expected water table.

- In drought-prone areas: consider a deeper well that reaches a confined or better-recharged aquifer.

- Look at historical well logs and local water-level data to estimate extremes.

Failing to account for seasonal lows can leave you with a pump that runs dry or a well that yields too little during critical times.

Legal and Regulatory Considerations

Local codes and permitting often dictate minimum depth, casing standards, setbacks, and construction practices.

Permits and Inspections

You’ll usually need a permit to drill a new well and to abandon an old one. Inspections and reporting requirements vary by jurisdiction.

Setbacks

Most areas specify minimum distances from septic systems, livestock yards, fuel tanks, and property boundaries. Adhere to these to protect water quality and meet code.

Well Abandonment

If an old well exists, it must often be properly sealed (grouted) per local standards to prevent cross-contamination between aquifers.

Contact your local health or environmental agency to get applicable rules for your location.

How Much Does Well Depth Affect Cost?

Cost is one of the main constraints. Drilling deeper increases costs for labor, rig time, casing, cementing, pump size, and materials.

Typical Cost Factors

- Rig mobilization/demobilization

- Drilling time (per foot rates)

- Casing and screen materials (steel, PVC)

- Grouting and sanitary seal

- Pump, control, and electrical installation

- Water testing and disinfection

Ballpark Cost Table (installed, USD)

| Item | Shallow Well (50–150 ft) | Deeper Well (150–400 ft) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drilling (per foot avg) | $15–$40/ft | $30–$60/ft | Varies by rock/soil type |

| Casing & screen | $1,000–$3,000 | $2,000–$6,000 | Diameter and material affect cost |

| Pump & start-up | $800–$2,500 | $1,500–$4,000 | Submersible pumps cost more for deep |

| Installation & plumbing | $500–$2,000 | $1,000–$3,000 | Includes electrical hookup |

| Permits, testing & disinfection | $200–$800 | $200–$800 | Varies locally |

| Typical total (installed) | $3,000–$8,000 | $6,000–$20,000+ | Highly variable by region |

These figures are estimates. Get several local quotes to compare.

Designing Your Well: Depth, Diameter, and Screen Placement

You’ll need a design that matches supply needs and geological conditions.

Well Diameter

Residential wells typically use 4–8 inch diameter casing. Larger diameters can allow higher yields and easier maintenance but cost more.

Screen Placement

Screen location and length determine how much of an aquifer you can access. A longer screen in a productive zone generally yields more water, but must avoid sand production or fine-grained collapse.

Casing and Seals

Proper sanitary seals and surface grouting prevent contamination from shallow sources. If you tap multiple water-bearing zones, you may need seals between them.

Your contractor should provide a well log showing depth, lithology, casing depth, screen intervals, and water levels.

Testing a New Well

After drilling, a well should be tested to quantify yield and quality.

Pump Test (Yield Test)

A constant-rate pump test for several hours to days assesses sustainable yield and drawdown. Results help size pumps and estimate sustainable pumping rates.

Water Quality Testing

Test for bacteria, nitrates, pH, hardness, iron, manganese, and any contaminants known for your area (e.g., arsenic, radon). Repeat testing annually or when problems arise.

Interpreting Tests

If the yield is insufficient, options include deepening the well, installing a larger pump (not recommended without sufficient yield), or drilling a new well at a better site.

Choosing the Right Well Contractor

Selecting a competent contractor is crucial. The right contractor will protect your investment and help you avoid future problems.

Credentials and Licensing

- Verify the contractor’s license and registration where required.

- Confirm bonding and insurance (liability and workers’ comp).

Experience and Local Knowledge

- Choose someone with experience in your local geology.

- Ask for references and visit recent installations if possible.

Written Estimates and Clear Contracts

- Get detailed, written estimates that include drilling depth range, casing type, pump type, yield guarantees (if any), timeline, and cleanup.

- Ensure the contract spells out who obtains permits and handles testing and reporting.

Warranties and Follow-up

- Ask about warranty on workmanship, casing, and pump.

- Confirm availability for service calls and maintenance.

Questions to Ask Potential Contractors

- How many wells have you drilled in my area?

- Can you provide well logs and permit documentation?

- What is your contingency plan if the initial depth fails to produce?

- Do you provide a pump test and water quality testing?

- What are your payment terms and warranties?

Contractor Checklist Table

| Item to Verify | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| License & insurance | Legal compliance and protection |

| References | Proof of competence |

| Local experience | Knowledge of local aquifers |

| Written estimate & contract | Clarity on scope and cost |

| Pump test & water testing | Ensures performance and safety |

| Warranty & service | Future support available |

| Permits handled | Saves you time and ensures compliance |

Site Selection and Setbacks

Where you locate the well on your property matters for both safety and performance.

Key Considerations

- Place the well uphill from potential contamination sources (septic systems, livestock pens, chemical storage).

- Maintain required setback distances per local code.

- Consider access for rig and pump service—avoid overly constrained locations.

- Think about freezing exposure and route of underground plumbing.

A good contractor will help you select the best spot and document reasons in the permitting process.

Common Problems and How Depth Affects Them

Understanding common well issues can help you avoid them or choose right-sizing measures upfront.

Low Yield or Dry Well

Often caused by insufficient depth or pumping out of a limited zone. Proper testing before final pump installation helps identify this.

Sand and Sediment Production

Occurs when the well screen intersects loose materials without adequate casing or filtering. Deeper, screened wells in bedrock or consolidated aquifers usually avoid this.

Contamination

Shallow wells are more vulnerable to surface contamination. Proper sealing and siting reduce this risk.

Pump Cycling and Pressure Problems

If the well doesn’t store enough water or has inadequate yield relative to pump capacity, you may get short cycling. Adjusting pressure tank size or reducing pump cycle frequency helps, but adequate well yield is the primary fix.

Maintenance and Long-Term Care

Proper care extends the life of your well and maintains water quality.

Routine Tasks

- Test for bacteria annually and after any system repairs.

- Check pressure tank function and pump operation periodically.

- Shock chlorinate the well if contamination is detected.

- Keep records of well logs, tests, and service visits.

When to Consider Deepening or Redrilling

- Persistent low yield despite rehabilitation.

- New contaminants appearing at shallow depths.

- Significant seasonal declines in water level that impact use.

Discuss long-term plans with your contractor so you can avoid short-term fixes that won’t meet future needs.

Practical Scenarios: How Deep Might You Need to Go?

Here are examples to help guide your decision based on typical use cases.

Single-Family Home, Moderate Use (2–4 people)

- Typical depth: 50–200 feet in many areas.

- Reason: Moderate demand; often enough to reach sand/gravel aquifer.

Large Household or Irrigation for Lawn/Garden

- Typical depth: 100–400 feet.

- Reason: Higher sustained demand requires higher-yield zones or deeper aquifers.

Remote Rural Property in Fractured Bedrock Region

- Typical depth: 200–600+ feet.

- Reason: Need to intersect fractures and provide stable supply; deeper drilling common.

Livestock Watering or Commercial Use

- Typical depth: 150–500+ feet.

- Reason: High sustained flows and reliability required.

Local conditions may change these recommendations significantly; use these as starting points.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How deep should a well be to avoid contamination?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Deeper wells are generally less vulnerable to surface contamination, but proper siting, casing, and sealing are equally important. In many places, reaching a confined aquifer or properly sealed deeper sand/gravel layer helps reduce contamination risk.

Can I add depth later if the well underperforms?

Yes. In many cases a contractor can deepen the well or drill a new one if yield is insufficient. That’s more expensive than drilling deeper initially, so planning ahead is wise.

How often should I test my well water?

Test for bacteria at least annually and after repairs. Test for other parameters (nitrates, metals, hardness) based on local risks or if you notice changes in taste, odor, color, or staining.

Will a deeper well always have better water quality?

Not always. Some contaminants (arsenic, radon, high salinity) are more common in deeper aquifers. Testing is essential regardless of depth.

Final Checklist Before You Drill

- Check local well depth averages and aquifer information.

- Obtain required permits and understand setback rules.

- Get multiple written bids from licensed contractors with local experience.

- Confirm the contractor will provide a well log, pump test, and water quality testing.

- Discuss long-term usage needs (household size, irrigation) to size depth and pump.

- Plan for well site access, security (lockable cap), and future maintenance.

Summary

You should select well depth based on local geology, seasonal water-level fluctuation, anticipated water demand, water quality considerations, and budget. Shallow wells are cheaper but more vulnerable; deeper wells increase the chance of reliable supply and different water chemistry but cost more and require different equipment. Work with experienced, licensed contractors who provide testing, written contracts, and follow local regulations to ensure a well that meets your needs for years to come.

If you want, you can provide your general location (state/region) and estimated water needs (household size, irrigation, livestock) and I can summarize typical depth ranges and likely issues for your area.