Are you worried that surface water, runoff, or activities near your property might contaminate your well water?

How Do I Protect My Well From Surface Contamination?

You depend on your well for safe drinking water, household use, and peace of mind. Protecting your well from surface contamination means controlling how water and pollutants move across and into the ground near the well, keeping the well structure intact and sealed, and testing and treating the water regularly so you know what you’re drinking.

Understand the risks from surface contamination

You should know what surface contamination is and why it matters. Surface contamination refers to pollutants that originate at or near the ground surface — such as bacteria from animal or human waste, fertilizers, pesticides, fuels, and road runoff — and that enter your well system. These contaminants can cause illness, damage plumbing and appliances, and make water unusable.

Recognizing the difference between surface water and groundwater pathways helps you focus protective measures. Surface sources are usually episodic (storm-driven, seasonal, or associated with specific activities) while groundwater contamination may travel more slowly but persist longer.

Common surface contamination sources

Knowing likely sources near your property helps you prioritize actions. Common contributors include:

- Septic systems and drain fields that are too close, failing, or overloaded.

- Agricultural runoff carrying fertilizers, manure, and pesticides.

- Livestock yards, manure piles, and animal congregation areas.

- Chemical or fuel spills, and leaking storage tanks.

- Roadways, where salt, oil, and other pollutants wash toward the well.

- Surface drainage and pond overflow, especially during storms or floods.

- Abandoned, unsealed wells that act as direct conduits.

- Nearby construction sites or stockpiles where materials are stored on soft ground.

Each source has different contaminants and pathways, so controlling the source is often the most effective protection.

How contamination moves from surface to well

Contaminants follow gravity and pathways of least resistance. Understanding those paths helps you prevent them. Typical routes include:

- Surface runoff traveling downhill to the wellhead or pooling around the casing.

- Cracks or gaps in the well casing, cap, or grout that allow surface water to flow down the borehole.

- Poorly sealed annular space (the gap between casing and borehole) enabling rapid downward flow.

- Shallow wells that intercept near-surface groundwater or perched water tables.

- Karst terrains and fractured rock where contaminants can travel quickly through conduits or fractures.

- Overwhelmed or poorly located septic systems that allow pathogens to move through soil to the well.

Contaminants can move quickly in some geologic settings, so siting, construction, and maintenance must match local hydrogeology.

Types of wells and their vulnerability

The type and construction of your well influence how vulnerable it is to surface contamination. Different well types include dug, driven, and drilled wells, each with distinct features and risks.

Dug wells

Dug wells are typically shallow and broad, often dug by hand or machine. Because they are shallow and have large openings, they are much more vulnerable to surface contamination and direct infiltration from runoff, flooding, and nearby sources.

If you have a dug well, you need especially rigorous surface drainage management, a secure well cap, and routine testing.

Driven wells

Driven wells use screened pipe driven into unconsolidated materials and are deeper than dug wells but shallower than many drilled wells. They can still be vulnerable where the water table is shallow, if the casing is corroded, or if the cap and seals are compromised.

Ensuring effective sanitary seals and maintaining surrounding drainage is important for driven wells.

Drilled bedrock wells

Drilled wells into bedrock tend to be deeper and less vulnerable to surface contamination than shallow wells. However, they are not immune; fractures and karst conduits can provide quick pathways. Proper casing, grouting, and a sanitary seal at the surface are essential for protection.

Regulations and local resources

You don’t have to rely only on general guidance. Local and state health departments, environmental agencies, and extension services provide specific regulations, setback requirements, and testing guidance tailored to your region.

Contact your county or state health department to:

- Learn required minimum setback distances and permitting procedures.

- Obtain local well-construction codes, approved materials, and licensed well-driller lists.

- Find free or low-cost testing programs, especially after floods or emergencies.

- Get guidance on required disinfection and well plugging procedures.

Having local regulations and resources at hand helps you make sure any work complies with rules and protects public health.

Siting and setting your well to minimize risk

Where your well is located relative to potential contaminant sources is one of the most effective controls you can set when you install or replace a well. Proper siting considers slope, distance to hazards, land use, and geology.

If you already have a well, evaluate nearby activities and whether any new developments (garages, septic fields, livestock areas) could reduce safe distances. If installing a new well, work with a licensed driller and local authorities to choose the best site.

Recommended setback distances

Setbacks vary by jurisdiction and local geology, but these general minimum distances are commonly recommended. Use them as starting points, then verify with local codes.

| Potential contaminant source | Recommended minimum distance (typical) |

|---|---|

| Septic tank | 50 to 100 feet |

| Leach/drain field | 50 to 200 feet |

| Property line (neighbor) | 10 to 50 feet |

| Livestock yards/manure piles | 100 to 300 feet |

| Barns or animal housing | 100 to 300 feet |

| Chemical/fertilizer storage | 100 to 300 feet |

| Fuel storage or above-ground tanks | 100 to 300 feet |

| Road or highway | 50 to 100 feet |

| Surface water body (pond/stream) | 50 to 200 feet |

These values are general: in karst or fractured rock, increase distances. Your local health department may require larger setbacks.

Construction features that protect from surface contamination

Construction quality matters as much as location. Proper materials and techniques prevent direct infiltration of surface water and maintain well integrity.

Key protective features include:

- Adequate casing material and depth to reach safe aquifers.

- Grouting and annular seals to fill the space between casing and borehole, preventing downward flow along the outside of the casing.

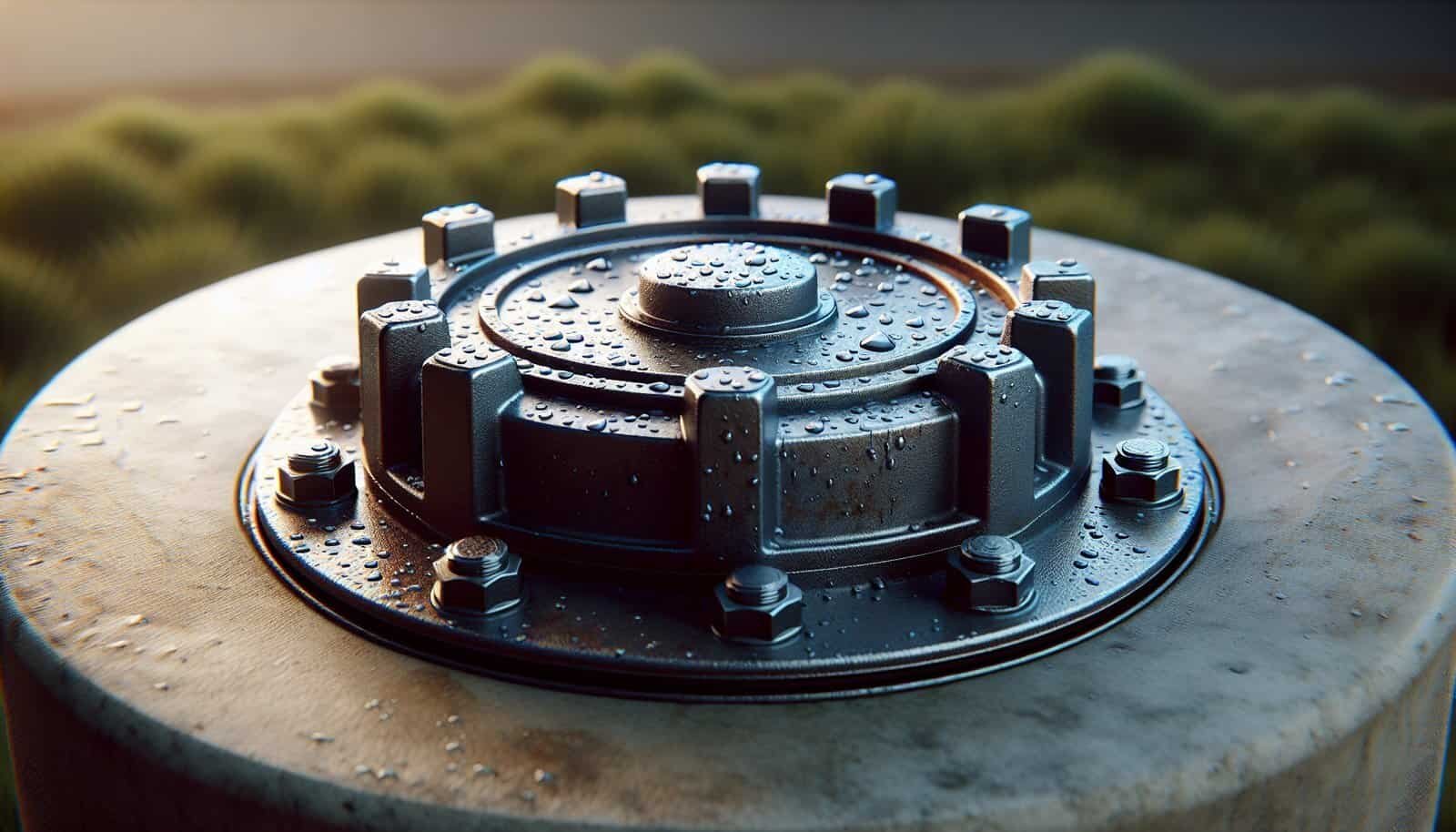

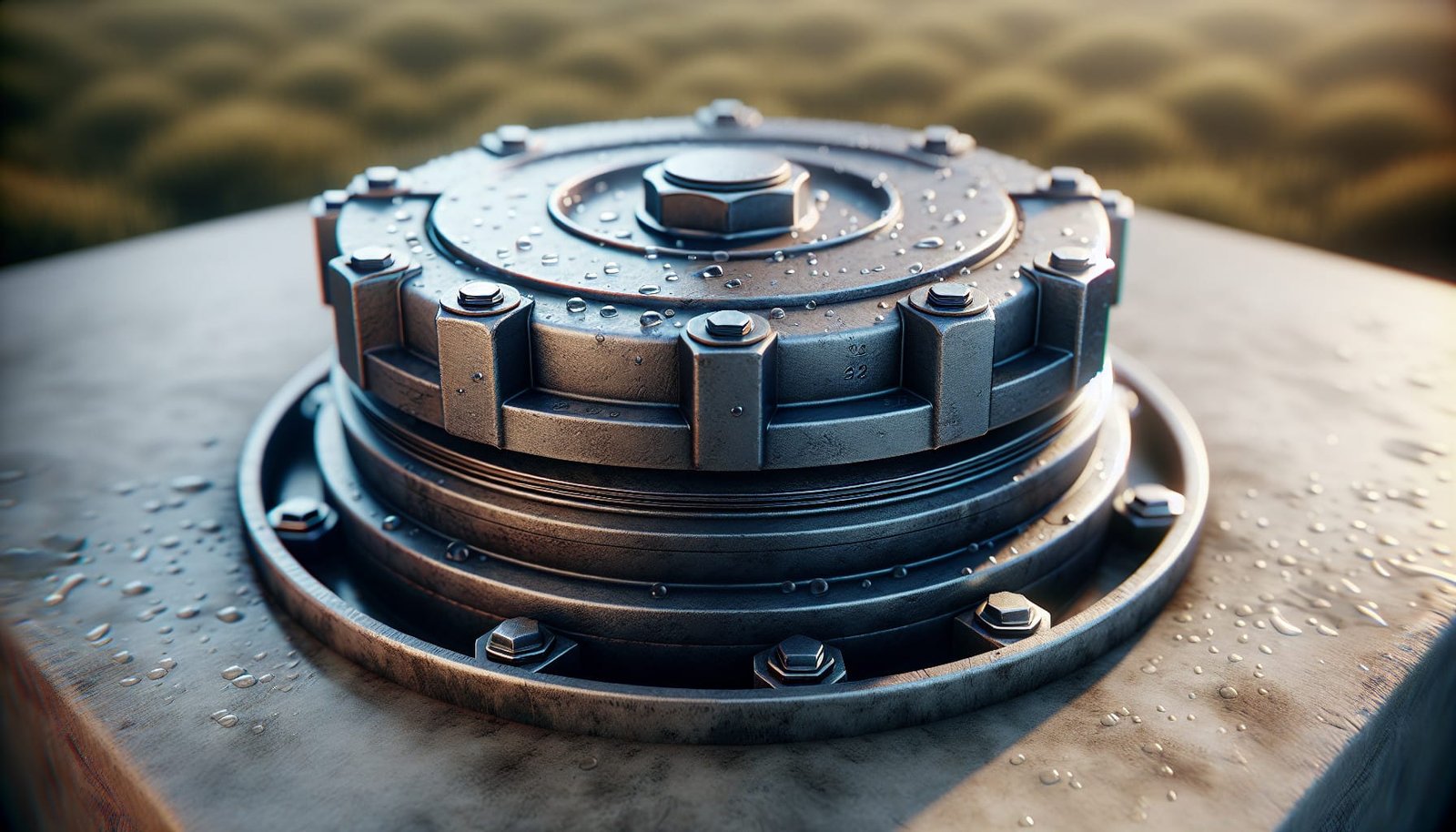

- A licensed sanitary well cap that resists intrusion by insects, small animals, and surface water.

- Casing that extends above ground sufficiently to prevent surface runoff entry.

- Surface seals and protective aprons to channel water away from the wellhead.

Well cap and sanitary seal

A watertight sanitary well cap prevents insects and small animals from entering and stops direct rain or surface water from flowing down the borehole. Make sure the cap is secure, in good condition, and fitted with a screened vent if needed.

Proper grouting and annular sealing

Grout, often bentonite clay or cement grout, fills the space between the well casing and the borehole. This grout must be installed to an appropriate depth to seal the shallow zones where contamination is most likely. An inadequately grouted annulus can allow rapid contamination movement.

Casing materials and depth

Casing material should resist corrosion and be sized to your local conditions (steel, PVC). Extend the casing above the ground surface at least 12–18 inches, ideally more if the area floods or accumulates snow. Ensure casing depth reaches below any contaminants or shallow perched water in the upper soil.

Surface drainage and landscaping

You control how surface water moves around the well site. Channeling water away and preventing pooling around the well is essential.

Best practices include:

- Grading the ground to slope away from the well (1–2% slope or more).

- Building a small berm or swale to divert surface runoff away from the well.

- Installing a concrete apron or well pad around the casing to prevent erosion and infiltration.

- Directing gutters, downspouts, and driveway drains away from the well.

- Avoiding planting water-attracting landscaping such as vegetable gardens directly upslope of the well.

Concrete slab and apron specifications

A concrete apron or slab provides a durable, non-porous surface around the well, minimizing infiltration and erosion.

- Size: at least 3 feet radius around the casing; many jurisdictions recommend 4 feet or more.

- Slope: slope apron away from the well at a minimum 2% grade.

- Thickness: typically 3–4 inches for a slab; thicker if subject to vehicle traffic.

- Seal: provide a caulked joint between the casing and the slab to reduce flow.

Confirm local codes for required dimensions and materials.

Maintenance and inspection schedule

Regular inspection and maintenance catch small problems before they become contamination sources. A proactive schedule makes your water safer and your well last longer.

Suggested routine:

- Monthly: Visually inspect the wellhead, cap, and casing for damage, open vents, or standing water near the well.

- After heavy storms or flooding: Inspect for damage, check for standing water, consider testing for coliform bacteria.

- Annually: Test water for total coliform bacteria and nitrate at a minimum; have the well interior and mechanical components inspected by a professional.

- Every 3–5 years: Test for a broader suite — iron, manganese, pH, hardness, TDS, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) if you are near potential sources.

- After any well repair, pump replacement, or contamination event: Shock chlorinate or disinfect the system and retest.

Maintenance checklist

| Task | Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Visual wellhead inspection | Monthly | Check cap, vent, casing, standing water |

| Surface drainage check | Seasonal | Ensure slopes and aprons remain intact |

| Bacteria & nitrate testing | Annually | More frequent if problems or risk factors |

| Mechanical pump inspection | Annual or by manufacturer | Watch for vibrations, noise, or loss of pressure |

| Full water quality panel | Every 3–5 years | Depending on local risks |

| Shock chlorination | As needed | After contamination or well service |

| Professional well inspection | Every 5–10 years | Based on well age and condition |

Keep records of all inspections, results, and repairs.

Water testing: what to test and how to interpret

Testing is the way to know whether your protection measures work. Regular testing tells you if bacteria, nitrates, or other chemicals are present and whether treatment is required.

Common tests and guidance:

| Parameter | What it indicates | Typical guideline / EPA standard | Action if detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total coliform bacteria | General bacterial contamination | None acceptable; presence indicates contamination | Stop using water for drinking/cooking until treated or bottled; disinfect and retest |

| E. coli (fecal coliform) | Recent fecal contamination (high risk) | None acceptable | Immediate action: use bottled/boiled water, disinfect well, repair source, retest |

| Nitrate (as N) | Fertilizer, manure, septic contamination | MCL = 10 mg/L as N | If >10 mg/L, do not use for infants or pregnant women; find source & treat or replace well |

| Nitrite | Recent contamination or septic issues | EPA action level = 1 mg/L | Similar to nitrates; acute health risk for infants |

| Turbidity | Particulates can shield microbes from disinfectants | Lower is better; <1 ntu desirable< />d> | Investigate source, consider filtration, disinfection |

| pH | Corrosivity, scaling | No MCL but 6.5–8.5 typically preferred | Adjust pH to protect plumbing and treatment systems |

| Total dissolved solids (TDS) | Overall mineral load affecting taste and scale | Secondary guideline ~500 mg/L (aesthetic) | May require RO or softening if high |

| Iron & manganese | Staining, taste, odor | Secondary standards for aesthetics | Install specific filters if problematic |

| Arsenic | Natural or industrial source | MCL = 0.010 mg/L (10 µg/L) | Treat with appropriate filtration (ion exchange, RO, adsorption) |

| Lead & copper | Corrosion from plumbing | Action levels: lead 0.015 mg/L, copper 1.3 mg/L | Address plumbing, corrosion control, treatment |

| VOCs (benzene, solvents) | Industrial spills, fuel leaks | Various MCLs; benzene 0.005 mg/L | Immediate investigation and treatment; may need point-of-entry systems |

If tests show bacterial contamination, assume immediate health risk. For chemical exceedances, consult a qualified water-treatment professional and local health authorities for specific actions.

Disinfection and treatment steps

If your well tests positive for bacteria or you suspect contamination, disinfecting may be necessary. Long-term treatment options are available for persistent chemical or taste/odor problems.

Shock chlorination (basic steps)

Shock chlorination can eliminate bacteria in many shallow or small contamination events. If you choose to perform it, follow safe procedures and local guidance. If you’re uncertain, hire a licensed well professional.

Basic outline:

- Calculate the well volume (based on depth and casing diameter) to determine required chlorine amount.

- Use household bleach (5–6% sodium hypochlorite) or a commercial chlorine product.

- Pour the calculated chlorine solution into the well and circulate the chlorinated water through all faucets until you smell chlorine at each outlet.

- Let the system stand for a minimum contact time (commonly 6–24 hours depending on contamination severity and local guidance).

- Flush the system until chlorine is no longer detectable and discharge to a location where chlorine will not harm plants, septic systems, or aquatic life.

- Retest for bacteria after chlorination and flushing — usually within 7–10 days.

Safety notes: Use protective gloves and goggles. Avoid mixing cleaning products, and observe local discharge rules.

Long-term treatment options

If contamination is persistent or chemical (nitrates, arsenic, VOCs), consider:

- Point-of-entry (whole-house) systems like activated carbon adsorption (for many VOCs), ion exchange (for nitrate), or reverse osmosis (for many dissolved contaminants).

- Ultraviolet (UV) disinfection for bacteria and viruses (requires low turbidity and proper maintenance).

- Continuous low-level chlorination systems for ongoing microbial control.

- Specialized media like iron filters, arsenic adsorption media, and others tailored to the contaminant.

Match treatment to the contaminant, and maintain systems per manufacturer instructions.

When to call a professional

There are times when professional help is the right choice:

- You get repeated positive bacteria results or E. coli detections.

- A large contamination event occurred nearby (chemical spill, agricultural spray, fuel leak).

- Physical damage to the well casing, cap, or pump has occurred.

- Your well was flooded.

- You need complex treatment for arsenic, nitrates, VOCs, or persistent iron/manganese issues.

- You need the well plugged or a new well drilled.

A qualified well contractor, licensed driller, or certified water treatment specialist can assess, repair, and implement remediation and compliant solutions.

Protecting your well during construction or remodeling

Construction activities pose an elevated contamination risk. Soil disturbance, heavy machinery, and materials can create pathways or generate pollutants.

Best practices:

- Keep construction materials, concrete washout, fuel, and chemicals well away from the well site.

- Cover and seal the well opening temporarily if work is nearby, ensuring the seal is sanitary and won’t trap contaminants.

- Keep a buffer zone and fence the well to prevent accidental damage.

- Maintain positive surface drainage around the well and avoid piling fill against casing.

- After construction, disinfect and test the well before resuming regular use.

Managing nearby land use

Your daily activities and how you manage your property influence well safety. Simple changes reduce risk.

Practical tips:

- Service septic systems regularly; avoid planting drain-field-permeable surfaces over fields.

- Store chemicals, fuels, and fertilizers on impervious surfaces and within secondary containment.

- Place livestock yards and manure storage farther from the well, and consider fences to prevent animals near the wellhead.

- Apply pesticides and fertilizers responsibly, do not spray upslope from your well, and follow label instructions.

- Maintain vegetative buffers or grass filter strips to slow runoff and encourage infiltration away from your well.

Small operational changes often prevent the largest risks.

Emergency actions after flooding or storms

Floods and major storms can overwhelm protective features and introduce contaminants. Act quickly if your well or surrounding land was flooded.

Immediate steps:

- Do not drink or cook with well water until it has been tested and declared safe by health officials.

- Use bottled water or boil water (boil for at least one minute if no chemical contaminants are suspected) for drinking, cooking, and brushing teeth.

- Inspect visible well components for damage and signs of intrusion.

- Remove debris and pump out standing water away from the well if safe to do so.

- Disinfect (shock chlorinate) the well and plumbing after flood waters recede, then retest before resuming normal use.

- Report chemical spills or suspicious contamination to local authorities and follow their instructions.

Always prioritize safety, and contact professionals for complex damage or contamination situations.

Abandoned and unused wells

Old, unused wells are serious hazards. They can act as direct conduits for surface contamination into deeper aquifers and pose physical risks.

You should:

- Identify any unused or abandoned wells on your property.

- Do not attempt to plug or modify abandoned wells yourself unless you are trained and permitted to do so.

- Contact your local health or environmental department for rules and reputable contractors who can properly plug wells per state standards.

- Proper plugging protects your aquifer and prevents animals or people from falling in.

Plugging is often required by law and helps protect both property and public health.

Record keeping and long-term planning

Good records help you track changes and detect problems early. Keep a water log for testing, repairs, and inspections.

What to keep:

- Well log and construction details (driller’s log, depth, casing, pump type).

- Testing results with dates and labs used.

- Records of treatments, repair work, and disinfecting events.

- Receipts and warranties for equipment and treatment systems.

- Maps showing well location relative to septic, drain fields, and potential contaminants.

Review records periodically, and plan for eventual pump replacement, well rehabilitation, or upgrades as part of long-term property maintenance.

Cost considerations and financing assistance

Cost varies by region and problem severity. Ballpark figures:

- Water testing (basic): $25–$150 per test depending on parameters.

- Shock chlorination: $100–$400 DIY or by a pro, depending on well depth.

- Drilling a new residential well: several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars depending on depth and geology.

- Installing a whole-house treatment system: $1,000–$10,000+ depending on technology and capacity.

- Plugging an abandoned well: $500–$2,500+ depending on complexity.

If cost is a concern, check local health departments, community action agencies, or state grant programs for assistance with testing, repairs, or replacement. Some states offer loans or cost-share programs for wells in underserved communities.

Checklist and quick action plan

Use this actionable checklist to protect your well from surface contamination:

- Inspect wellhead monthly for cracks, open vents, or standing water.

- Ensure the well cap is tight and intact; replace damaged caps immediately.

- Keep at least the recommended setback distances from septic tanks, livestock areas, and chemical storage.

- Grade land and build aprons to send surface water away from the well.

- Maintain vegetative buffers upslope and avoid planting gardens immediately upslope.

- Test for total coliform and nitrate annually; more often if risk factors exist.

- Shock chlorinate after flooding, repairs, or positive bacterial tests, then retest.

- Service septic systems regularly and keep tanks pumped on schedule.

- Seal or plug abandoned wells through a licensed contractor.

- Contact your local health or environmental department for local rules, testing resources, and licensed well professionals when in doubt.

Summary and final guidance

Protecting your well from surface contamination is about prevention, good construction, routine maintenance, and timely testing. You can do a lot on your own: watch the wellhead, manage surface drainage, maintain proper setbacks, and test regularly. For structural issues, repeated contamination, or complex chemical problems, rely on licensed professionals and your local health authority.

If you take practical, consistent steps, you reduce risks significantly and keep your water supply healthier for your household for years to come. If you’re unsure about a particular situation, contact your local health department or a licensed well professional — they can offer site-specific advice and help you implement the right solution.